I wrote an earlier posting “DC Power Supply Common Mode Noise Current Considerations”

(click here to review) as common mode noise current can be an issue in electronic test applications we face. This is not so much of an issue with all-linear based power supply designs as it can be for ones incorporating switching based topologies. High performance DC power supplies designed for test applications should have relatively low common mode current by design. I thought this would be a good opportunity to get some more first-hand experience validating common mode noise current. The exercise proved to be a bit of an eye-opener. I tried different approaches and, no surprise; I got back seemingly conflicting results. Murphy was busy working overtime here!

I settled on a high performance, switching-based DC source on having a low common mode noise characteristic of 10 mA p-p and 1 mA RMS over a 20 Hz to 20 MHz measurement bandwidth. To properly make this measurement the general consensus here is a wide band current probe and oscilloscope is the preferred solution for peak to peak noise, and a wide band current probe and wide band RMS voltmeter is the preferred solution for RMS noise. As the wide band RMS voltmeters are pretty scarce here I relied on the oscilloscope for both values for the time being. The advantages of current probes for this testing are they provide isolation and have very low insertion impedance.

I located group’s trusty active current probe and oscilloscope. The low signal level I intended to measure dictated using the most sensitive range providing 10 mA/div (with oscilloscope set to 10 mV/div).

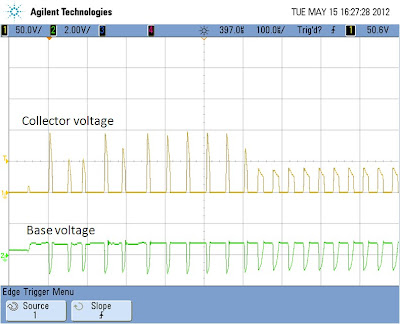

One area of difficulty to anticipate with modern digital oscilloscopes is there are a lot of acquisition settings to contend with, all having a major impact on the actual reading. After sorting all of these out I finally got a base line reading with my DC source turned off, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Common mode noise current base-line reading

My base-line reading presented a bit of a problem. With 1 mV corresponding to 1 mA my 2.5 mA p-p / 0.782 mA RMS base-line values were a bit high in comparison to my expected target values. It would be nicer for this noise floor to be at about 10X smaller so that I don’t have to really factor it out. Resorting to the old trick of looping the wire through the current probe 5 times gave me a 5X larger signal without changing the base-line noise floor. The oscilloscope was now displaying 2 mA /div, with 1 mV corresponding to 0.2 mA. In other words my base-line is now 0.5 mA p-p / 0.156 mA RMS. The penalty for doing this is of course more insertion impedance. Now I was all set to measure the actual common mode noise current. Figure 2 shows the common mode noise current measurement with the DC source on.

Figure 2: Common mode noise current measurement

Things to pay attention to include checking the current on both + and – leads individually to earth ground and load the output with an isolated load (i.e. a power resistor). Full load most often brings on worst case values. Based on the 0.2 conversion ratio I’m now seeing 8 mA p-p and 1.12 mA RMS, including the baseline noise. I am reasonably in the range of the expected values and having a credible measurement!

I decided to compare this approach to making a 50 ohm terminated direct connection. This set up is depicted in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: 50 ohm terminated directly connected common mode noise current measurement

I knew insertion impedance was considerably more with this approach so I tried both 10 ohm and 100 ohm shunt values to see what kind of readings I would end up with. Table 1 summarizes the results for the directly connected measurement approach.

Table 1: 50 ohm terminated directly connected common mode noise current results

Clearly the common mode noise current results were nowhere near what I obtained with using a current probe, being much lower, and also highly dependent on the shunt resistor value. Why is that? Looking more closely at the results, the voltage values are relatively constant for both shunt resistor cases. Beyond a certain level of increasing shunt resistance the common mode noise behaves more as a voltage than a current. For this particular DC source the common mode voltage level is extremely low, just a few millivolts.

Not entirely content with the results I was getting I located a different high performance DC source that also incorporated switching topology. No actual specifications or supplemental characteristics had been given for it. When tested it exhibited considerably higher common mode noise than the first DC source. The results are shown in table 2 below.

Table 2: 50 ohm terminated directly connected common mode noise current results, 2nd DC source

With both voltage and current results changing for these two test conditions the common mode noise is exhibiting somewhere between being a noise current versus being a noise voltage. I had hoped to see what the results would be using the current probe but it seemed to have walked away when I needed it!

In Summary:

Making good common mode current noise measurements requires paying a lot of attention to the choice of equipment, equipment settings, test set up, and DUT operating conditions. I still have bit more to investigate but at least I have a much better understanding as to what matters. Maybe in a future posting I can provide what could be deemed as the “golden set up”! To get results that correlate reasonably with any stated values will likely require a set up that exhibits minimal insertion impedance across the entire frequency spectrum. Making directly coupled measurements without the use of a current probe will prove challenging except maybe for DC sources having rather high levels of common mode noise currents

The underlying concern here of course is what is what will be the impact to the DUT due to any common mode noise current from the test system’s DC source. Generally that is any common mode noise current ends up becoming differential mode noise voltage on the DUT’s power input due to impedance imbalances. But one thing I found from my testing is that the common mode noise is not purely a current with relatively unlimited compliance voltage but somewhere between being a noise voltage and noise current, depending on loading conditions. For the first DC source, with what appears to be only a few millivolts behind the current it is unlikely that it would create any issues for even the most sensitive DUTs. For the second DC source however, having 100’s of millivolts behind its current, could potentially lead to unwanted differential voltage noise on the DUT. Further investigation is in order!