In the first part of this posting (click here to review) I

highlighted what kind of response time is important for effective over current

protection of typical DUTs and what the actual response characteristic is for a

typical over current protect (OCP) system in a test system DC power supply. For

reference I am including the example of OCP response time from the first part

again, shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Example OCP system response time vs. overdrive

level

Here in Figure 1 the response time of the OCP system of a

Keysight N7951A 20V, 50A power supply was characterized using the companion

14585A software. It compares response times of 6A and 12A loading when the

current limit is set to 5A. Including the programmed OCP delay time of 5

milliseconds it was found that the actual total response time was 7

milliseconds for 12A loading and 113 milliseconds for 6A loading. As can be seen, for reasons previously

explained, the response time clearly depends on the amount of overdrive beyond

the current limit setting.

As the time to cause over current damage depends on the

amount of current in excess of what the DUT can tolerate, with greater current

causing damage more quickly, the slower response at lower overloads is

generally not an issue. If however you

are still looking how you might further improve on OCP response speed for more

effective protection, there are some things that you can do.

The first thing that can be done is to avoid using a

power supply that has a full output current rating that is far greater than

what the DUT actually draws. In this way the overdrive from an overload will be

a greater percentage of the full output current rating. This will normally

cause the current limit circuit to respond more quickly.

A second thing that can be done is to evaluate different

models of power supplies to determine how quickly their various current limit

circuits and OCP systems respond in based on your desired needs for protecting

your DUT. For various reasons different models of power supplies will have

different response times. As previously discussed in my first part, the slow

response at low levels of overdrive is determined by the response of the

current limit circuit.

One more alternative that can provide exceptionally fast

response time is to have an OCP system that operates independently of a current

limit circuit, much like how an over voltage protect (OVP) system works. Here

the output level is simply compared against the protect level and, once

exceeded, the power supply output is shut down to provide near-instantaneous

protection. The problem here is this is not available on virtually any DC power

supplies and would normally require building custom hardware that senses the fault

condition and locally disconnects the output of the power supply from the DUT.

However, one instance where it is possible to provide this kind of

near-instantaneous over current protection is through the programmable signal

routing system (i.e. programmable trigger system) in the Keysight N6900A and

N7900A Advanced Power System (APS) DC power supplies. Configuring this

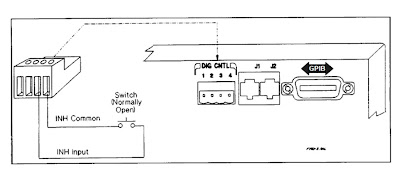

triggering is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Configuring a fast-acting OCP for the

N6900A/N7900A Advanced Power System

In Figure 2 the N7909A software utility was used to

graphically configure and download a fast-acting OCP level trigger into an

N7951A Advanced Power System. Although this trigger is software defined it runs

locally within the N7951A’s firmware at hardware speeds. The N7909A SW utility

also generates the SCPI command set which can be incorporated into a test

program.

Figure 3: Example custom-configured OCP system response

time vs. overdrive level

Figure 3 captures the performance of this

custom-configured OCP system running within the N7951A. As the OCP

threshold and overdrive levels are the same this can be directly compared to

the performance shown in Figure 1, using the conventional, current limit based

OCP within the N7951A. A 5 millisecond OCP delay was included, as before.

However, unlike before, there is now virtually no extra delay due to a current

limit control circuit as the custom-configured OCP system is totally

independent of it. Also, unlike before, it can now be seen the same fast

response is achieved regardless of having just a small amount or a large amount

of overdrive.