I was having a discussion here with a colleague about the

merits of powering a high brightness LED (HBLED) using pulsed power versus

using steady state DC power.

My opinion was: “Basically, amperes in proportionally equates

to light flux out, so you will get about the same amount of illumination

whether it is pulsed or DC.”

His argument was: “Because the pulses will be brighter,

it’s possible the effective illumination that’s perceived will be brighter.

Things appear to be continuous when discrete fixed images are updated at rates

above thirty times a second, and that should apply to the pulsed illumination

as well!”

I countered: “It will look the same and, if anything,

will be less efficient when pulsed!”

So instead of continuing our debate we ran a quick

experiment. I happened to have some HBLEDs so I hooked one up to an N6781A DC

source measure module housed in an N6705B DC Power Analyzer sitting at my desk,

shown in Figure 1. The N6781A has excellent current sourcing characteristics

regardless whether it is DC or a dynamic waveform, making it a good choice for

this experiment.

Figure 1: Powering up an HBLED

First we powered it up with a steady state DC current of

100 mA. At this level the HBLED had a forward voltage drop of 2.994 V and

resulting power of 0.2994 W, as seen in Figure 2, captured using the companion

14585A control and analysis software.

Figure 2: Resulting HBLED voltage and power when powered

with 100 mA steady state DC current

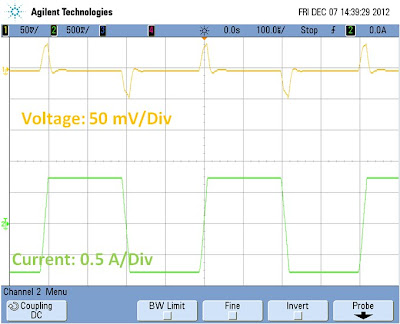

We then set the N6781A to deliver a pulsed current of 200

mA with a 50% duty cycle, so that its average current was 100 mA. The results

were again captured using the 14585A software, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Resulting HBLED voltage and power when powered

with 200 mA 50% DC pulsed current

Switching back and forth between steady state DC and

pulsed currents, my colleague agreed, the brightness appeared to be comparable

(just as I had expected!). But something

more interesting to note is the average current, voltage, and power. These

values were obtained as shown in Figure 3 by placing the measurement markers

over an integral number of waveform cycles. The average current was 100 mA, as

expected. Note however that the average voltage is lower, at 2.7 V, while the

average power is higher, at 0.3127 W! At first the lower average voltage

together with higher average power would seem to be a contradiction. How can

that be?

First, in case you did not notice, the product of the RMS

voltage and RMS current are 0.3897 W which clearly does not match our average

power value displayed. What, another contradiction? Why is that? Multiplying

RMS voltage and RMS current will give you the average power for a linear

resistive load but not for a non-linear load like a HBLED. The average power

needs to be determined by taking an overall average of the power over time

computed on a point-by-point basis, which is how it is done within the 14585A

software as well as within our power products that digitize the voltage and

current over time. Second, the average voltage is lower because it drops down

towards zero during periods of zero current. However it is greater during the

periods when 200 mA is being sourced through the HBLED and these are the times

where power is being consumed.

So here, by using pulsed current, our losses ended up

being 4.4% greater when powered by the comparable steady state current. These

losses are mainly incurred as a result of greater resistive drop losses in the

HBLED occurring at the higher current level.